James Webb Telescope Collides With Asteroid Cloud, Severely Damaged

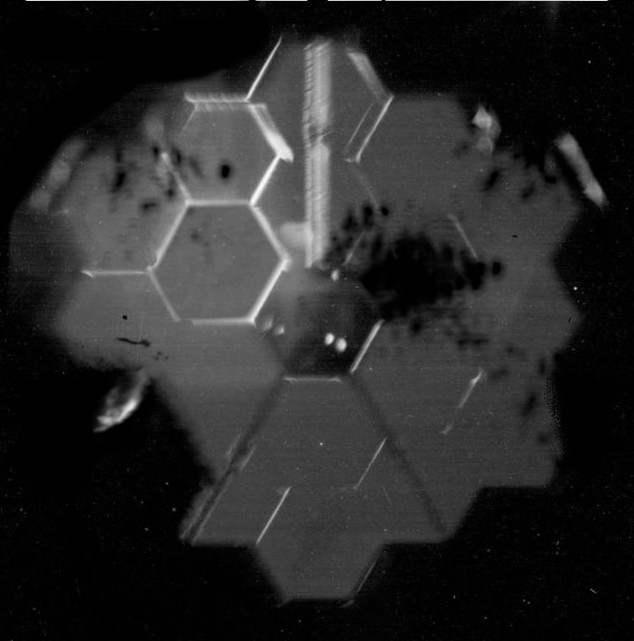

The James Webb Space Telescope sustained severe damage to its primary mirrors as an undetected asteroid cloud collided with the telescope. The surviving transmission antenna and camera used for mirror alignment returned this photo after emergency signals were received by NASA late on March 31, 2022. NASA hide caption

"A deeply heartbreaking moment for the scientific community," said John Mather, Senior Project Scientist for the James Webb Telescope.

"We continue to receive and review data, but recent images reveal severe damage to the primary mirrors and therefore chances that the telescope will be able to fulfill its intended mission are extremely small."

This devastating news comes less than one month after NASA reported that the 18 separate mirror segments had been precisely aligned, a major milestone in the initiation of the project.

The $10 billion infrared telescope launched in December after decades of development and construction, and it thrilled astronomers when it successfully unfolded itself out in space. It was not planned to begin full operation until later this summer when it would gather light showing how the first galaxies looked, just a couple of hundred million years after the Big Bang.

"The mirrors were designed to be able to function with 20 percent of their surface damaged in order to ensure smooth operation over the lifespan of the telescope. Unfortunately they have lost over 50 percent of their surface area during this collision and much of the alignment hardware has been damaged," said Mather.

Additionally, reports of temperature spikes on the "dark" side of the instruments indicate that the complex multilayered heat shield has also been damaged.

NASA says that the positioning thrusters are still functioning and the telescope is maintaining its orbit. Additionally, with communications still online, they will continue to evaluate the extent of the damage and determine if any of the secondary instruments can provide usable data over the coming months.

Could this have been prevented?

"The challenge with these asteroid clouds is that no single object is larger than a baseball," says Paul Abell, Chief Scientist for Small Body Exploration within the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division at the Johnson Space Center. "Our detectors can easily confuse them with background noise, and that is exactly why we were unable to detect the cloud that hit the James Webb Telescope."

Rather than a single large rock that affects light detectors in a predictable way, clouds of hundreds of thousands of small pieces of asteroids ranging in size from dust to baseballs can appear only as extremely faint signals in a very busy sky.

Additionally, while a large rock may have clipped the telescope and damaged a single part of its mirrors, the cloud acted like the spray from a shotgun, creating a large area of major and microscopic damage.

"We continue to improve our detection systems every year, but they will never be one hundred percent perfect, and this is an unfortunate and gut wrenching example of how bad luck can set back a field of study by decades," says Abell.