Another Dinosaur That Never Exsited: This Time The Spinosaurus

Arcterosaurus (skeleton at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh), is what paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh originally found before adding the spines and calling the Spinosaurus. Joshua Franzos/Carnegie Museum of Natural History hide caption

Arcterosaurus (skeleton at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh), is what paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh actually found when he thought he'd discovered the Spinosaurus.

Joshua Franzos/Carnegie Museum of Natural HistoryAnother dinosaur finds itself being escorted out of the history books.

Over the last several decades, archeologists have had the opportunity to re-evaluate the "correctness" of our beloved dinosaurs, using new fossils and improved technology to tease out the details of our prehistoric predecessors. Names and figures such as Iguanodon, Cetiosaurus, Hypsilophodon, and more recently the iconic Brontosaurus have all fallen into never-existed'dom as scientists revaluated the data that built them in the first place.

Now, next on the chopping block is the Spinosaurus.

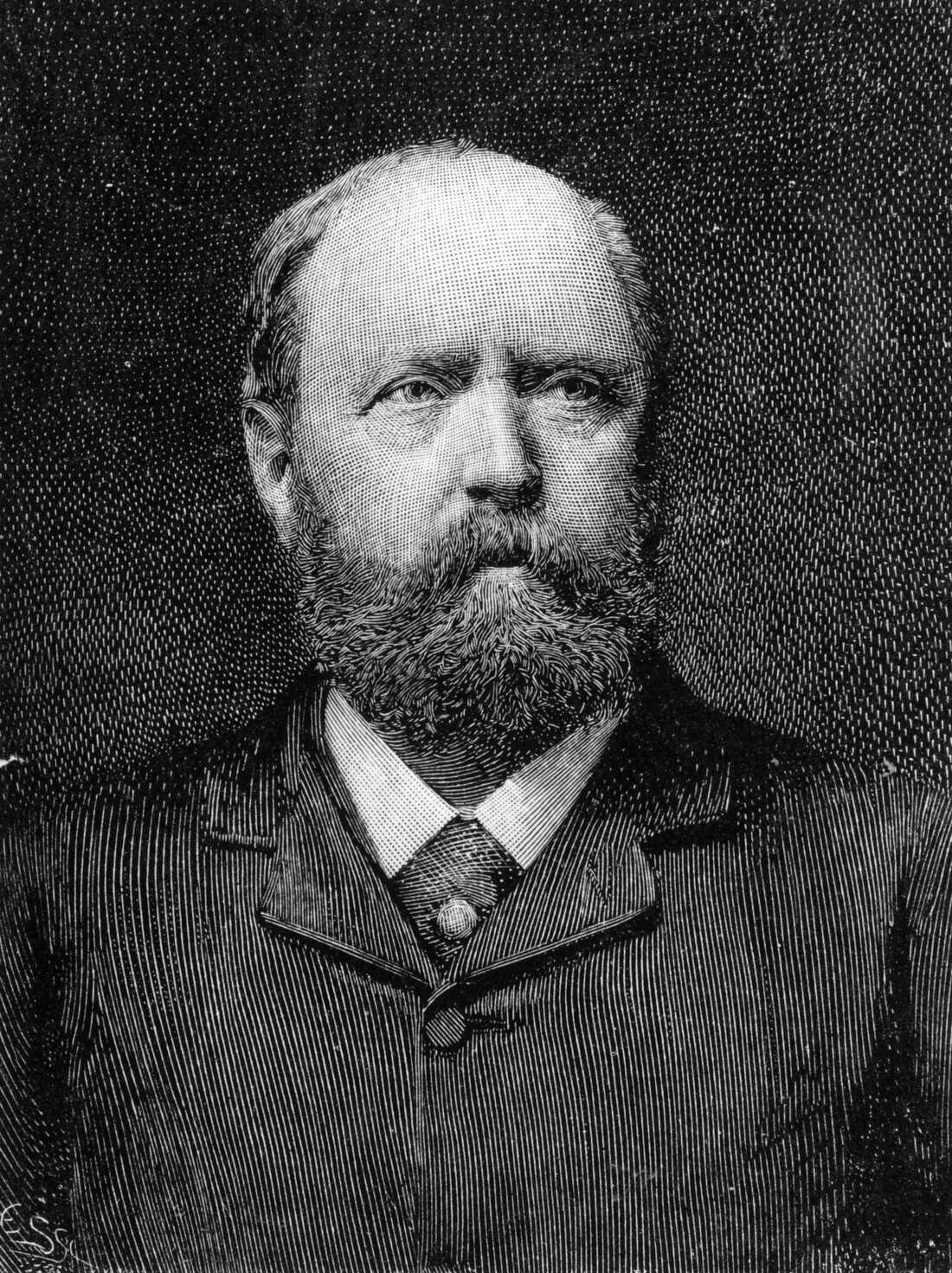

Othniel Charles Marsh was a professor of paleontology at Yale who made many dinosaur fossil discoveries, including the Arcterosaurus (formerly Spinosaurus). Hulton Archive/Getty Images hide caption

Despite its appearance in Jurassic Park films and being shown at museums around the world, scientifically speaking, there's no such thing as a Spinosaurus, or at least in the way that the skeletons have been reassembled and portrayed over the years.

It dates back 130 years, to a period of early U.S. paleontology known as the Bone Wars, says Matt Lamanna, curator at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh.

The Bone Wars was the name given to a bitter competition between two paleontologists, Yale's O.C. Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope of Philadelphia. Lamanna says their mutual dislike, paired with their scientific ambition, led them to race dinosaur names into publication, each trying to outdo the other.

"There are stories of either Cope or Marsh telling their fossil collectors to smash skeletons that were still in the ground, just so the other guy couldn't get them," Lamanna tells Guy Raz, host of weekends on All Things Considered. "It was definitely a bitter, bitter rivalry."

The two burned through money, and were as much fame-hungry trailblazers as scientists.

It was in the heat of this competition, in 1877, that Marsh discovered the partial skeleton of a long-necked, long-tailed dinosaur with distinctive spines, which were supposedly long extensions of the vertebrae he dubbed Arcterosaurus.

"The spines we see today were not present at the excavation site," Lamanna says, "they were actually found at a nearby site by Drinker's team who then let Marsh know via a quite provocative letter."

Embarrassed that he had missed such a major part of the skeleton, he quickly paid a sum of $3,000 to acquire the spines, equivalent to over $500,000 in today's money.

Marsh added the spines, which vaguely appeared to have been attached to the vertebrae, vertically along the spine to give a prominent and intimidating appearance. This was a major mistake.

Although the mixup was theorized by scientists by 1903, the Spinosaurus lived on, in movies, books and children's imaginations with so few fossils (all found by Marsh) to prove that it was wrong. The apathy of the scientific community and a dearth of well-preserved Arcterosaurus skeletons kept it unchanged for over 100 years.

Now, new 3D scans have revealed that the spines were not part of the original skeletons at all.

Rather, the new theory is that the spines were part of a calcareously spiked reptile that was a food source for the Arcterosaurus - hence why piles of the spines were found in the same archeological sites as the Arcterosaurus.

Museums are now trying to figure out how to approach editing the fictional Spinosaurus skeletons to bring them back to their anatomically correct Arcterosaurus state.